A conversation during the first UK Lockdown about boredom and mourning change with Sean Hall, Lecturer at Goldsmiths London.

A candid conversation between me and Gweni Llwyd through Green Man’s Artists Talking series in August 2020.

New York Arts Magazine. The St. Ives New School. July/ August 2005, vol10, no 7 & 8. Written by Max Andrews who was at that time Curatorial Assistant to Director, Tate and Curatorial Fellow Walker Art Centre Minneapolis.

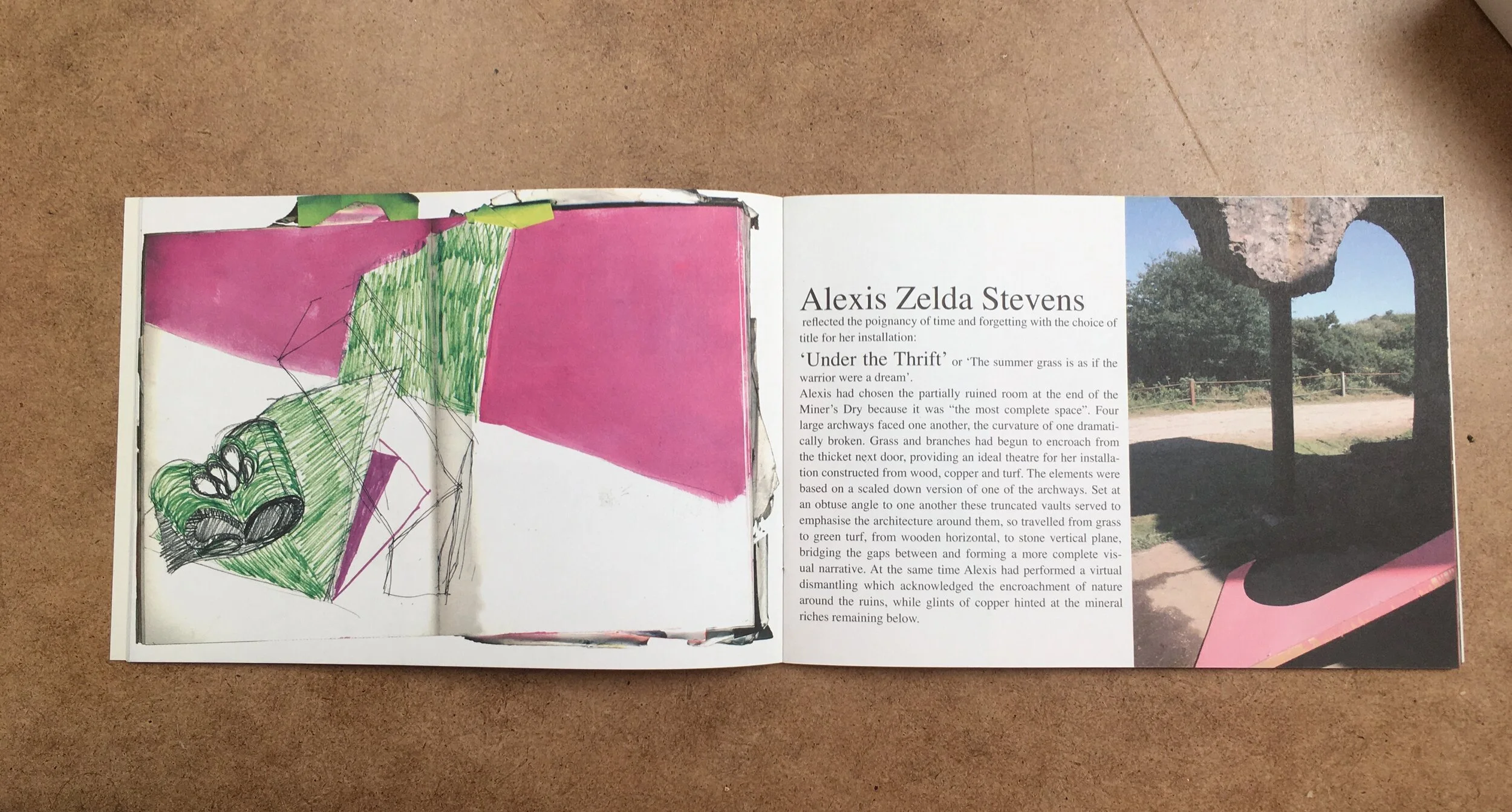

The mode of practice that Alexis Zelda Stevens has consolidated during her residency at ArtSway is precarious and precocious; and it might have begun with a pink-painted branch or a dinky green ladder. The former protruded inelegantly from a deliciously clashing orange painting in Interior Landscape II (2004), one of the works in her painting degree show at Falmouth College of Arts. The latter, salvaged from a skip in the town, became a sort of studio buddy and a totem or taboo of object-ness.

Poking through a gash in the canvas, the candy-pink branch literalised a conceptual transition in Stevens’s artistic practice that is now fully realised in her two-gallery-filling installation for ArtSway. Her puncturing of this picture-surface started off as a silly, wonky gesture that seemed to mock the seriousness of the task at hand. Yet the act was a chromatically charged provocation to the authority of the canvas, and the trigger to consider working in three-dimensions more profoundly. The immediacy of the appeal of the green ladder played its part too, suggesting a scavenging approach that could make use of whatever came to hand. At the culmination of her degree, Stevens had questioned the sustainability of producing the ‘proper’ paintings implied by an educational doctrine that was marinated in medium-specificity, latent concepts of expressive realism and visual language.

It would be disingenuous of me to suggest that Stevens is a necessarily Cornish artist. Though having studied at Falmouth College of Arts for a year myself in the mid 1990s, I feel as good as justified in divining that the heritage of the St. Ives School that comprised Peter Lanyon, Ben Nicholson, Patrick Heron, Barbara Hepworth et. al., with the push and pull of Constructivist formalism on the one hand and narrative plus symbolism on the other – all mashed together with the blissful naïveté of Alfred Wallis and a heady experience of landscape – must remain a forceful and wonderfully overdetermined field that looms over the eminent painting department of its region. In other words Stevens’s first forays away from painting inevitably meddled in their own unassumingly subversive way with the approved lineage of Cornish modern (landscape) painting.

Previously pursuing a generative, cumulative working process that resourced from photographs and sketchbooks to the end point of a large canvas, she first turned her back on the landscape by resisting the greens and blues so evocative of land and sky-sea, and adopted instead an expanded palette of more artificial colours – fluorescent puce and orange, emergency yellow and alien green. And from not only puncturing the canvas to go on to abandon it altogether, Stevens began to make constructions and accumulations of painted objects and found materials, working things out in studio space rather than on picture space.

Peter Lanyon made several three-dimensional structures using painted and coloured glass in his studio near St. Ives in the 1950s. These were at first conceived as disposable developmental devices, tools to aid the composition of his paintings, yet he went on to exhibit constructions as works of art in their own right. Stevens’s mapping of a compositional process into the gallery transposes this turn in Lanyon’s work, similarly unpicking the already-there into the constitution of a finished work. Yet the developmental precedent for Stevens’s current approach is located away from the studio or classroom entirely. The artist was home schooled until the age of nine (her parents are both artist-educators) following a trans-disciplinary, creative way of learning. The approach favoured by this home baked Montessori Method is now distilled in Stevens’s unlearning of painting’s phantom curriculum. She is relearning to learn through exploration and, in an approximation of the singer-songwriter, scavenging-making with fluid, haptic exercises, combinations of rehearsal and composition, noodling and doodling, storytelling and picturing.

The artist’s current work for ArtSway is an alarming balancing act. Her adoption of unremarkable objects and materials – concrete, timber, chair parts, mirrors, electrical tape, brightly coloured laundry line – take us well beyond the insistent mysticism of canvas and stretcher, yet abstract painting – or abstraction and paint – remains a way in for the viewer. Here the term Plasticism might denote both the compositional ‘science’ of Constructivist ecstasy, and at the same time the evolution of High Density Polyethylene milk bottles into organic forms. Her use of easily recognisable matter and materials as major elements in the otherwise formal arrangements deliberately teases the abstract credibility by the suggestion of narrative interpretations. With the introduction of (real) lights and shadows and the possibility of the viewer acting within them instead of standing passively in front of them, chiaroscuro space becomes a real space that’s somewhat domestic, possibly theatrical and potentially threatening.

In her refusal of the canvas as a host for product, and in her tempered avoidance of popular cultural imagery, Stevens wills a kind of anti-consumerist utopian compositional community into existence in the galleries together with an urgent use of colour. Nevertheless the practical ingredients of painting as a noun – support and surface – are still to be found, though sometimes they are literally hanging on by a thread. Structures made from two-by-one inch timber, the favoured college material for painting stretchers of course, have infiltrated her new aesthetic lexicon where they are pressed into service as surrogate, canvasless entities. Tolerated like enthusiastic and benign zombies as the remnants of a painting that haunts these three-dimensional workshop-like spaces and refuses to die quietly, timber lengths are indelibly daubed with orange gloss paint – somewhat tarred if not quite feathered – and are suspended or made to lean as if in stress positions. Despite this effective deconstruction, evisceration or humiliation of painting on canvas, Stevens’s attitude is not pre-critical or too coy, nor does it ever abandon painting as a verb. It is not as blunt an instrument as Angela de la Cruz’s mangled monochromes, but it is neither too precious.

An acknowledged powerful influence on Stevens’s emerging practice is the work of Seattle-born Jessica Stockholder, whose colourful room-filling installations developed from 1983 while studying painting at Yale University. Following Stockholder, Stevens works intuitively though not necessarily as a direct response to site. Where Lanyon and his constructions at first struggled to find their own independence from his mentor Naum Gabo, Stevens too has squirmed with the anxiety of influence. In what amounts to her rediscovery of the self-directed sensibility of her childhood educational experience however, Stevens easily elides any obligations to mastery.